Our first guest contributor! Welcome, Hershal, to the wonderful world of armchair pseudo-intellectual speculation, loosely held together by pithy titles and out-of-nowhere rhetorical questions! Isn’t it great?

I see you did some research on procrastination – I did as well. This week, I spent countless hours on the internet perusing various flavours of instant gratification instead of focusing on other, more pressing, matters (like this post). Completely unlike any other week, I swear. Here’s one article I stumbled upon. It’s a facinating read about a Russian family, the Lykovs, of ‘Old Believers’ that fled from the atheist Bolshevik purges of Christianity in the 1930s. The Lykovs escaped into the Russian Taiga, a harsh wilderness that’s cold and barren in the winter, and full of dark clouds of mosquitoes in the summer. Amazingly, the family of four (growing to six, after two more children were born in the wilderness) managed to live on their own with no human contact until 1978, completely unaware of World War II, space travel, or nuclear weapons. When the father was shown a cellophane container by a party of geologists who made first contact, he exclaimed ‘Lord, what have they thought up—it is glass, but it crumples!’.

I bring this up to highlight two points. First, a meta one. Procrastination does sometimes lead to bits and pieces of wonderful new knowledge like the fascinating story of Old Believers. How much do I retain during a typical procrastination-induced binge? I don’t know, probably not much. But I do enjoy breaking up the monotonous routine that often seems like the way you’re supposed to live your life. Plan out your schedule, do everything the schedule says, and be a good little robot. Procrastination is the antithesis to the schedule, it’s a way for me to be anti-programming (to use Rachit’s phrase he coined during our life and death segment). Are you ok with never knowing about the Lykovs, in exchange for a few hours of more peaceful sleep? I’m not. But maybe I’m that rat that’s checking for new knowledge constantly, instead of scheduling a one hour binge session once a week? The ‘b’ word may or may not be applicable here.

Second, the Lykovs could not have procrastinated much. How could they? Their lives, and the lives of their entire family were at stake. Procrastination is a product of a societal safety net, something that does not exist in the harsh Siberian wilderness. From an evolutionary perspective, procrastination doesn’t make much sense. We procrastinators should have died out ages ago. Where are all the lions surfing the safari-equivalent of Reddit? They’re dead. As humans, we procrastinate because we can, but when push comes to shove, we get shit done. In some ways this thought is a relieving one: we are programmed by millions of years of evolution to survive, to live until we can reproduce. I’m sure everyone’s heard the advice that’s given to entrepreneurs, artists, and other people looking to start a long, intimidating journey: just put yourself out there, and commit yourself fully. Just do it, as Nike has been saying for decades. Sure, it’s trite, but it makes sense. Fear is the ultimate motivator, it triggers a response that has been hardwired into our brain: get shit done.

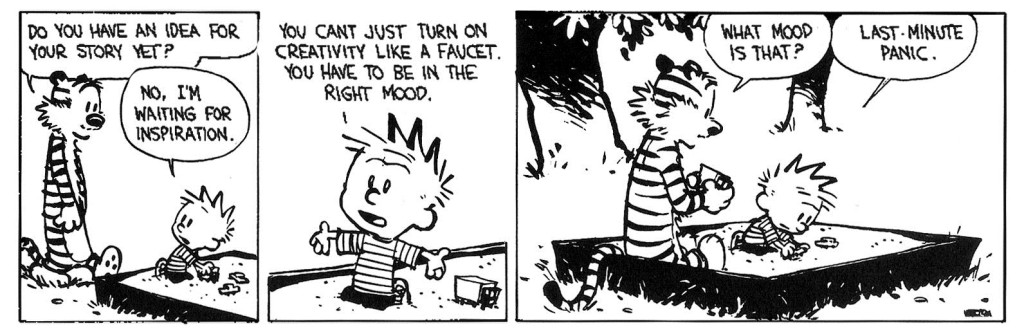

I have a few more thoughts I’d love to share, but in the interest of space, I’ll end it here and leave you with my one of my favourite comics of all time:

~ V